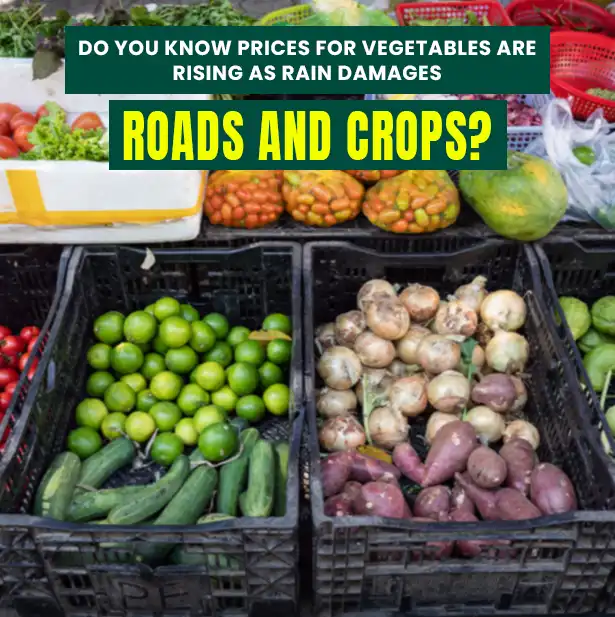

Rising vegetable costs are causing concern throughout India, as ongoing heavy rains are destroying fields and disrupting transportation infrastructure. The increasing prices for basic vegetables such as onions, tomatoes, and leafy greens clearly demonstrate the impact of these weather disturbances in both rural and metropolitan markets. This state of affairs captures the careful equilibrium among market stability, crop output, and weather patterns.

In vital vegetable-producing states including Maharashtra, Karnataka, Himachal Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh, prolonged and unseasonal rain have ruined standing crops. Farmers' inability to harvest in time due to waterlogged fields has led to decaying produce. Sensitive vegetables such as tomatoes, leafy greens, chillies, and capsicums are the most severely damaged, as excessive moisture encourages fungal diseases and pest infestations.

This crop loss has led to a surge in prices, thereby reducing the availability of fresh vegetables in wholesale markets. Many cities now have tomatoes, which few weeks ago sold for ₹30–40 per kg, now more than ₹100 per kg. Likewise, another staple—onions—have seen their prices increase to ₹70 per kg, and leafy vegetables are now rare. Farmers worry that more delays in harvesting would affect quality, therefore lowering their market worth even if supply recovers at once.

Another major difficulty is getting veggies to metropolitan areas and wholesale marketplaces. Delays in deliveries result from damaged rural roads and highways brought on by heavy rain. Usually, fresh produce rots on route due to inadequate infrastructure and long distances. These logistical problems have aggravated the situation since markets deal with two challenges: disrupted deliveries and reduced supply.

The volume of arriving veggies has decreased by more than 30%, according to several wholesale traders at markets in Delhi and Mumbai. Retailers pass these extra transportation expenses on to customers, therefore increasing the price. Smaller cities and rural communities especially suffer since these locations usually depend on supplies from bigger agricultural hubs.

The increase in vegetable prices is significantly straining household finances. Many middle- and lower-income households are cutting back on their consumption of perishable vegetables; thus, they find it difficult to keep their normal diets. Basic ingredients for daily cooking—onions, tomatoes, and potatoes—have evolved for some households into luxuries. Until costs level out, many homes are replacing fresh veggies with pulses or shelf-stable items.

Small restaurants and street vendors that mostly rely on reasonably priced vegetables are also finding it difficult to manage increasing expenses. Some have trimmed down their menus or raised their pricing, therefore limiting customer choices.

In reaction to the crisis, the government started releasing onion buffer supplies in order to help stabilize prices. Should this situation persist, we may see similar measures for tomatoes and other essential vegetables in the future. States are also collaborating with transportation authorities to repair damaged roads and guarantee more seamless flow of products.

However, these initiatives are time-consuming, and they rarely result in instantaneous reductions.

As an additional method to distribute products, the government has also pushed e-commerce sites and farmer-to-consumer markets. This guarantees that some customers might cut reliance on conventional supply networks by directly accessing vegetables straight from farms.Rising prices would imply increased earnings for farmers, but the truth is more complicated. Their financial obligations have grown from crop damage, more re-sowing fees, and pest management costs. Many farmers are still healing from past disturbances, including irregular monsoons or droughts, which further inhibits their capacity to make investments in the following crop cycle.

Continuous rain has reportedly forced farmers in Maharashtra and Karnataka to postpone planting their kharif crops, especially vegetables. This delay might influence future supply, therefore extending the period of high pricing. Furthermore, many farmers face financial hardships due to their inability to obtain insurance or reimbursement for crop losses.

Although prices can drop as fresh crops hit the market and the monsoon season ends, experts stress the importance of long-term measures to lessen the effect of weather disturbances on agriculture. Better drainage in agricultural fields, improved forecasting systems, and investments in rural infrastructure can reduce future crop losses. Furthermore, encouraging cold storage facilities locally will help reduce waste and improve the shelf life of perishable veggies.

To better negotiate erratic weather patterns, more farmers are also investigating climate-resilient farming techniques, including crop diversification and greenhouse farming. However, these modifications require training and expenditure, and their widespread implementation may take some time.

The increase in vegetable prices brought on by rain-related disturbances shows how sensitive agriculture is to severe storms. Although government actions can provide some immediate assistance, the issue demands more strong infrastructure, improved storage options, and climate-resilient farming methods. Until these steps are implemented, farmers and consumers will continue to bear the brunt of these disturbances.

This crisis also reminds us of the interdependence of urban life and agriculture, which makes long-term stability dependent on addressing issues all across the food supply chain.